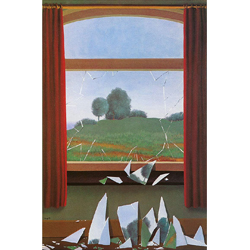

The image accompanying this post is my favorite painting, “The Human Condition” (La Condition Humaine) by Belgian artist Rene Magritte. And it was a favorite long before I knew that I am autistic. It spoke to me for reasons I didn’t understand yet.

But what does that have to do with masking?

What is masking?

Let’s take a step back and define the term masking. Masking, or camouflaging, is the term that is used to describe the ways that autistic people consciously change their behavior to seem more neurotypical. Everybody adapts their behavior to fit their environment. If you are at a job interview, and the interviewer asks “Why do you want to work here?” you don’t give the honest answer “I don’t, but I need money to survive.” If you are on a first date, you don’t spend an hour describing your collection of celebrity toenails. You know what is acceptable and what is likely to cause rejection, and you steer toward acceptable.

Some people use the term “code switching” to describe shifting from persona to persona depending on the circumstances. A work persona that dresses, acts, and speaks in certain ways can change into an after-work persona that dresses, acts, and speaks in completely different ways. Anyone who has worked in retail has their “customer service voice.” The way you talk to your boss is not the same as the way you talk to your friends. Or your family. Or strangers.

So if everybody adapts their behavior to fit the situation, why talk about it?

Because masking takes on an entirely different meaning for autistic people. It isn’t easy to explain, but I’m going to try.

Why do we mask?

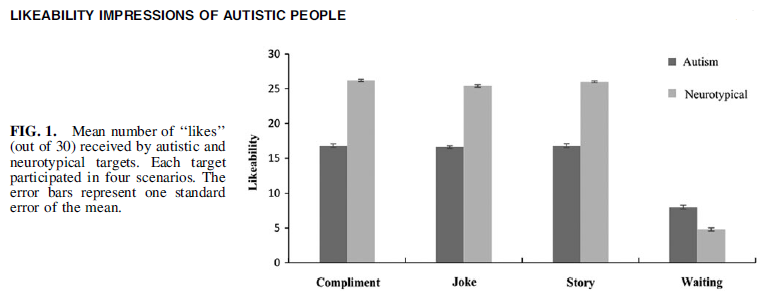

First, the simple fact is that the vast majority of neurotypical people don’t like autistic people. I’ll come back to my personal experience later and start with some objective truth from the appropriately titled paper “Do Neurotypical People Like or Dislike Autistic People?” [Alkhaldi RS, et al. Autism Adulthood. 2021 Sep 1;3(3):275–279]

Spoiler alert: if the answer was “neurotypical people LOVE autistic people,” then I probably wouldn’t have brought it up.

The authors of the paper recruited 30 neurotypical volunteers (“perceivers”). The perceivers watched 40 videos with an average length of less than eight seconds each. The videos showed one-on-one interactions between a research assistant and male participant. Half of the people the research assistant interacted with were autistic; half were neurotypical.

The videos covered four scenarios:

— the research assistant telling a joke to the participant

— the research assistant asking the participant to wait while he finished another, unrelated task

— the research assistant giving the participant a compliment

— the research assistant complaining about how bad their day was

After watching each video, the perceivers were asked “Do you like this person (yes or no)?”

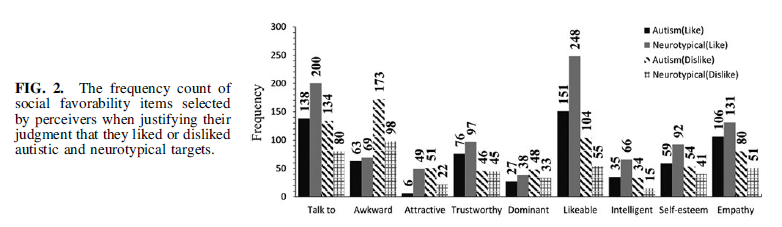

And then they were asked to rate the following on a scale of 1 to 6:

— How much would you like to talk to this person?

— How awkward is this person?

— How attractive is this person?

— How trustworthy is this person?

— How dominant is this person?

— How likable is this person?

— How intelligent is this person?

— How good is this person’s self-esteem?

— How empathic is this person?

Autistic people were consistently less liked. About 26 out of 30 neurotypical people were “liked” in three out of four scenarios presented in the videos, but only about 16 out of 30 autistic people were “liked” in those same scenarios. Only in videos where the autistic person was asked to wait were autistic people more liked. Apparently we are good at sitting quietly in an agreeable manner.

Autistic people received worse scores in all of the sub-categories. The paper states “The most common reasons selected by neurotypical perceivers when judging they disliked autistic targets were (1) the perceived awkwardness of the target, (2) a desire not to talk to the target, (3) target appearing unlikeable, and (4) the target’s perceived ability (or lack of ability) to empathize.”

Let’s recap. Based on less than eight seconds of a recording of an autistic person interacting with the research assistant, the perceivers made the following judgements:

- About 53% of the autistic people were liked, compared to about 86% of the neurotypical people

- Autistic people were rated 31% lower in the category “how much would you like to talk to this person?”

- Autistic people were rated 10% worse in “how awkward is this person?”

- Autistic people were rated 87% lower in “how attractive is this person?”

- Autistic people were rated 21% lower in “how trustworthy is this person?”

- Autistic people were rated 28% lower in “how dominant is this person?”

- Autistic people were rated 39% lower in “how likable is this person?”

- Autistic people were rated 46% lower in “how intelligent is this person?”

- Autistic people were rated 35% lower in “how good is this person’s self-esteem?”

- Autistic people were rated 19% lower in “how empathic is this person?”

This is my life. This is the life of many, many autistic people. And this is why we mask. Because 8 seconds after you meet us, you’ve already decided that we are awkward, unattractive, untrustworthy, passive, unlikeable, unintelligent, and / or unfeeling. And that we have low self-esteem.

OK. Let’s take a quick break. Here is a picture of a baby duck as a palate cleanser. The image is in the public domain as described at the Wikimedia Commons.

The view from this side of the mask

Neurotypical people don’t like autistic people. Largely because we are different and you don’t understand us. But the other side of that coin is that we don’t understand you either. The things you do and say make no damn sense. We are all playing a game, but nobody told the autistic people the rules. Or even the goal of the game. Or how to keep score.

How do all of you know the things you know, and why do those things make sense to you? Don’t ever say “Everybody knows that,” because I can assure you that not everybody does.

I remember a relationship that ended because she said to me “I shouldn’t have to tell you what I want.” At that moment, the only words that existed in my brain were “How am I supposed to know what you want if you don’t tell me?” Those were the wrong words. But they were true nonetheless.

I’ve learned to speak a little bit of neurotypical. I know that when you say “Can you do this?” you really mean “Do this” and the only acceptable answer is “yes.” And I also know that if I ask any follow up questions regarding what or how or why or when, you’re going to get frustrated and say “Can you do it or not?” And then I will get frustrated because I’ve already answered that question. But we play by your rules, not mine.

And don’t ever say “You know what I mean.” Because I don’t. I know what you said. If what you said doesn’t match what you mean, then that’s on you. I’m doing my best to work with the information that you have chosen to provide. If you want a different response, give me better information.

I know that you want eye contact. I’m not clear on why you want that, but you do. Eye contact can make me incredibly uncomfortable, but we play by your rules. I’m very good at eye contact. I know exactly how long to maintain it. When to look away. Where to look when I look away. When to look back again. But I can’t hear anything that you are saying because I’m busy counting off “Look away … two … three … four … And look back … two … three … four … five … six … seven … eight … Look away …”

You want eye contact and sympathetic nods and agreement noises. You want me to sit up straight and keep my hands still and keep my feet still. And I can do all of that. Or I can listen to you and think about what you are saying. But I can’t do both. And your rules say it is more important for me to look like I’m listening than to actually listen. Which makes no damn sense, but we play by your rules, not mine.

We mask because you don’t like us. We mask because somehow you got to write all the rules. Even though you won’t share them with us. But what’s the big deal? What’s the harm in a little masking if it makes everyone’s life easier?

The Telescope by Rene Magritte

The cost of masking

Nobody explicitly taught me to mask. But there were a thousand little lessons. Sit still. Don’t talk back to me (aka “Don’t ask why”). Look at me when I’m talking to you. Go give your grandmother a hug.

And, of course, school is a great place to learn to mask. Because in school, being different is the absolute worst thing that you can be.

And so I learned that the person I was was unacceptable. I needed to be somebody else. Somebody normal. Except I couldn’t be that. I didn’t know the rules. Even when I thought I did know the rules, I didn’t have the skills to follow them. Shockingly, the constant judgement and rejection, the inability to be who I thought I needed to be, and the sheer exhaustion from tying to be that other person led to some less than ideal outcomes.

So what’s the problem with masking?

Well, first of all, it doesn’t work as well as we think it does. There are just too many rules and too many things that neurotypical people do without thinking about it. If someone smiles at you, you smile back. Instantly. Because that’s the rule. But the window is very, very small.

If I take a second or two to process the fact that you are smiling, think through the fact that I should smile, decide how much I should smile, and then smile, it’s too late. And now I’m the freak who took too long to smile. Or you get offended, wondering why I had to think about whether I was going to smile or not. The end result is the same. I’m not one of Us. I’m a Them.

Things are going to slip through the mask. Some day I’m going to be too tired or too stressed or too distracted to hold the mask in place and you are going to see something that you are NOT ready for. Or I’m going to feel the mask slipping and leave the room quickly and without explanation. Which, again, makes me a Them. What’s wrong with That Guy? Where’s he going? He just walked out in the middle of a conversation.

Again, that’s not just my personal experience. There are studies to back up the fact that the mask can be easy to see through. One study states that “masking didn’t change the judgements that non-autistic peers made towards autistic people’s social behaviors. Even when an autistic person is masking, non-autistic people will still rate them more harshly than non-autistic peers if they don’t know they are autistic. This unconscious bias is evident throughout society for anyone deemed to behave or think atypically by neurotypical standards.” (From “Autistic people and masking” by Dr Hannah Belcher)

So there’s that.

But there are other, more serious problems with masking beyond the fact that it doesn’t work.

The second problem with masking is that it is exhausting. Pretending to be somebody else all day takes an incredible toll. And it can take hours to recover from a day of this effort. And if I don’t get my recovery time, then masking is just going to be that much harder the next day. If use more energy than I can replace for enough days a row, then I fall into burnout.

The idea of autistic burnout is complicated, but here are the highlights.

First: imagine that you are driving your car. With you are the 3 people who you consider the most annoying people in the world. You have been stuck in the car with them, in the worst rush hour traffic imaginable, for the past 2 hours. You’re angry. You’re stressed. You had plans to do something great this evening, but that’s not going to happen now. And if ANYBODY says ONE MORE WORD you are going to stop the car, switch it off, wander off into traffic and see how that goes. Take about 4 cups of that mixture of rage, frustration, and desire to be alone and put it in a large stock pot. Bring to a low boil.

Next, I need you to get on a treadmill. Set it to 1 mile per hour and walk on it for 48 hours straight. I’ll allow the occasional bathroom break. But no sleep, and only what you can eat or drink on the move. No TV or books or podcasts or whatever you use to make the time pass. Gather up the resulting physical and mental exhaustion. Add in the sense that you’ve been working forever and getting nowhere. Add 6 cups of this mixture to the stock pot.

Add one cup each of depression, hopelessness, isolation, and self-judgement.

Now that you have the stock, you can start adding your custom ingredients. Mine include a pair of hearing aids from the 1970s or 1980s that make sounds extremely loud, but also distorted and unpleasant. Some eyedrops to dilate my pupils to make even normal light a little too bright. A generous portion of insomnia. Several handfuls of irritability, especially toward anyone who might be foolish enough to try to help. Salt and pepper to taste.

Reduce until it is so dark and thick that you can’t see through it. Now live on that as your only source of nourishment while you continue to try to mask and do all of the things that you “should” be doing.

After a few weeks, you may begin to understand what autistic burnout feels like.

Palate cleanser part two. This image is available under a Creative Commons license as described at the Wikimedia Commons.

But back to the topic of masking: Masking generally doesn’t work as well as we think it does, and it’s exhausting. And there are other reasons why masking may not be the best plan.

1. Masking can take away a person’s sense of “self.” If you spend all of your time and effort trying to be who other people think you should be, then you don’t have the time or energy to figure out who you really are.

2. Masking is isolating. I’ve been masking for decades. When I started trying to tell a select group of family and friends that I am autistic, the almost unanimous response was “No you’re not.” They would cite accomplishments in my life, or the absence of what they considered autistic behavior as proof. And trying to convince someone that you really are autistic when they don’t want to believe it is about as exhausting as masking.

3. Masking can make it difficult for autistic people to be identified as autistic. I’ve seen a lot of therapists through the years for a lot of reasons. Only one even suggested that I consider the fact that I might be autistic. When I went in to be assessed for autism, I also asked for an assessment for ADHD. I scored much closer to “normal” on that assessment than I expected to. The therapist said the score was due in part to the fact I didn’t fidget or move during the ADHD assessment. Of course I didn’t move. I have 50 years of “be still” echoing in my ears. Moving is bad.

4. Masking is shame-based. A lot of the thinking behind of masking is “the person that I am is not acceptable.” And when you tell yourself that all day, every day, you believe it.

5. The exhaustion, isolation, shame, self-judgement, and everything else that is wrapped up in masking can have a big effect on someone’s mental health. As I said, I’ve seen a lot of therapists. I have fairly encyclopedic first-hand knowledge of antidepressants. And I’ve stood on the edge of The Void, taken a long look over the edge, and considered stepping off. Which is a story (or stories) for another time.

Estimates vary, but some studies suggest that autistic adults are nine times more likely to die by suicide than “normal” adults. Suicide is reported to be the second most common cause of death for autistic adults.

(If you are autistic [or not] and considering suicide, talk to someone. The issues you are facing are real, and talking alone won’t solve them. But not talking about them definitely won’t solve them. There may be help or compassion out there, but you won’t find it if you don’t look. In the US, you can find help here.)

So that settles it, then. Masking is bad and nobody should ever do it. Except life isn’t that easy.

Some autistic people don’t mask because they can’t. Autism is complicated. My version of autism results in behaviors that can potentially be masked. On a good day, in the right context, I can adjust my behavior to something close enough to what you consider “normal” so that you won’t notice. So long as we don’t interact for any great length of time.

I’ve been doing this for 50 years. I’ve learned a thing or two. Somewhere near the top of that list is the fact that most people are too self-centered to notice the people around them.

But some people’s behavior is not so “easily” hidden. Some autistic people are non-verbal or have language-processing issues. Those people might be able to nod and act as if they are listening to a conversation, but may not be able to speak.

Some autistic people have sensory issues and are either too sensitive or not sensitive enough to their physical environment. And this can go beyond sight and sound to the other senses that allow a person to maintain their balance or make small, controlled muscle movements. The resulting behaviors are hard to hide.

I’m 55 years old, and every day I care a little bit less about what “they” might think. Whoever “they” may be. And I still mask. At least a little. Almost always.

Sometimes it is a question of conserving my strength. If some fine, upstanding individual makes a crude comment about an autistic person, do I really want to spend the energy to try to explain autism to him? Especially if it is clear that he isn’t going to learn anything or make any changes to his behavior?

Sometimes I mask out of a sense of self preservation. I started a new job eons ago. On Day 1, I walked into the HR Director’s office and told her that I was autistic and talked about things that I needed. That was a terrible decision. As I’ve said, I’m very bad at reading subtext, but even I could see the fear and revulsion on her face.

I don’t know if she thought I was about to explode or if she thought that autism is contagious or if she thought I was about to start flinging poop. But she could not get me out of her office fast enough. That was fairly soon after I realized that I was autistic, and her reaction shaped the way I saw myself for a long time.

And sometimes the need for self-preservation is far more literal. I’m not qualified to talk about this, but there are some absolutely terrifying statistics about the rate at which autistic women are abused physically or sexually. Some studies report that autistic women are at three times greater risk than neurotypical women. Some studies report that up to 90% of autistic women have been the victims of domestic or sexual violence.

(If you are in this situation, you do not deserve whatever is being done to you. You deserve help. Please reach out to someone whenever and however it is safe to do so. In the US, you can find help here or here.)

What have we learned so far?

- Masking causes tremendous physical, mental, and emotional harm to autistic people who choose to mask.

- Masking is, among other things, a defense mechanism that autistic people use to avoid physical, mental, and emotional harm.

So now what?

I’m not a doctor or a therapist. I don’t have any particular training that qualifies me to tell people what they should do. What I have chosen to do is to mask less where possible. I haven’t quite figured out what that looks like yet. But here are 2 thoughts I’d like you to consider.

(1) Dropping the mask doesn’t have to be all or nothing.

I’m going to use the word “disclosing” to be the opposite of “masking.” “Disclosure” is a scary word for autistic people. It means telling the world who we are, having some difficult conversations, and accepting unknowable consequences.

But you can disclose in baby steps.

Let’s say you have sensory processing issues and there is some noise at work that makes it impossible for you to think. You could go to your boss and explain that you are autistic and have sensory processing issues and ask that your boss do something about the noise that doesn’t seem to bother anyone else. Let’s call that Plan B.

For Plan A, tell your boss that you are able to be the most productive in a quieter environment that lets you focus on your work. Ask for permission to bring in earplugs from home and wear them at work. Now you’ve given your boss a way to increase your productivity at no cost to him. That’s a deal he is definitely going to consider. You didn’t tell your boss that you are autistic. You didn’t have to have an embarrassing conversation about sensory processing issues. You found a small way to make life just a little bit better, and all it cost you was a box of earplugs.

That one step isn’t going to transform your life. And there are some issues that require bigger solutions. But if you can find a neutral way to discuss your needs — clear written instructions, time to think before answering a question, whatever — you can make progress. And it gives you a chance to evaluate your boss’s response. If the boss is open to a small step like earplugs, maybe it is safe to bring up another small step. And then a medium-sized step.

Taking the sources of stress or anxiety out of your environment doesn’t make the mask go away. But maybe it makes the mask a little lighter. A little easier to wear. Maybe having some control over your environment builds your self confidence. Maybe it starts a conversation. Maybe it inspires someone you work with who has the same struggles but doesn’t know how to talk about them.

It isn’t an easy or quick or absolute solution. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth doing.

(2) It is easy to say that autistic people should unmask as much as possible with as many people as possible. But this can be a huge challenge. We aren’t good at understanding what the people around us are thinking. We don’t know if any particular person can be trusted or how they might react to the word “autism.” Even in the middle of the conversation, or after the conversation is over, we still won’t know.

And we’ve been burned so many times. Because we communicate literally, we can be gullible. Liars and tricksters and manipulators love us. Because we believe what they say. That’s how our brains are wired.

If someone offers to sell me a bag of magic beans, there is a very real chance that I’m going to go home with a bag of magic beans. The nice, honest-looking man said they were magic, and I could use some magic, and buying the beans seemed to be the only way to end the conversation.

Being able to let the mask down requires knowing who to trust, and we don’t know who to trust.

Keeping the mask on means a long, slow grinding pain that wears us down. Taking the mask off means risking the sharp, intense pain of rejection or ridicule. Or worse. And we’ve made our choice that the long slow pain is preferable.

But there is always that chance that we might let the mask down a little and receive some understanding and support. This will, of course, make us suspicious that you are going to hurt us somehow, and so the mask will likely go back up again.

If you are neurotypical, and someone who is autistic lets their mask down a little, just let it be. Don’t criticize, obviously. But don’t celebrate either. Because the autistic person is likely to read your celebration as criticism. Because we aren’t good at reading the room. Just accept that this autistic person is trying to be more authentic with you, and deal with them where they are. Throwing them a parade will only make them run in terror. “Talking About It” is never Plan A for an autistic person. Just let it be. Let the autistic person lead the conversation, if any.

If you are autistic, think about this. My therapist asked me “if masking is so hard, then why do you do it.” I told him that I don’t like the way people treat me when they find out that I’m autistic. That I don’t like the way they see me or talk to me. Or stop seeing me or stop talking to me. I don’t like being seen as Other, not human, mechanical, alien. I don’t want to be Mr. Spock.

To which my therapist replied, “But people love Mr. Spock.”

And some people do.

To the autistic people reading this, do your best to find those people who will accept you. Not “autism acceptance month” accept. But genuinely accept. You will make mistakes. You will get hurt. But these people exist. Inside the autistic community and outside. And being genuine with them can reduce the weight of your mask and make you feel connected to the world.

The Door to Freedom by Rene Magritte

This was one of the main sources I was introduced to when I joined LinkedIn and has been a tremendous help in unpacking myself as I am. I always thought I was broken and not supposed to be here. But thanks to all the people I have met on LinkedIn, and the constant new flow of information that falls into place like missing pieces of a puzzle, I am on a sturdier road than I was before. Thanks to David Gunter and all the other magnificent autistic and ADHD people like me that fought for years to help themselves and others like me.

Thank you, Alex. That means a lot. I remember those days of feeling isolated and feeling inferior to everyone else. My main idea behind being more vocal about my autism was that I want to say the things that I wish someone had said to me 30 years ago.