The terms “neurodiversity” and “neurodivergence” are not interchangeable. For the purpose of this discussion, I’m going to start with an example related to height rather than autism. It’s not a perfect analogy, but bear with me.

“Diverse” applies to large groups of people. If we were to round up a billion people and ask them “How tall were you on your 21st birthday?” we would get a broad range of answers. Some people would say 4 feet 10 inches (147 cm). Some would say 5 feet 8 inches (172 cm). Some would say 6 feet 4 inches (193 cm). And we would get dozens of other answers. The human race in general is diverse when it comes to height at the age of 21.

A single person is not diverse. A single person was a certain height on their 21st birthday, and that will never change. But a single person might be divergent. If we gathered the responses about height from a billion of people and graphed them out, most would fall within a certain range. Some would not.

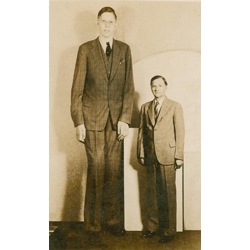

The picture accompanying this post is of Robert Wadlow. He holds the world record for tallest person in recorded history, with a height of 8 feet 11.1 inches (272 cm). He wore size 37 shoes. That’s 37 in US sizes, where 12 is considered large. I can’t find a chart that will convert a US size 37 to sizes for any other country. For reference, the tallest professional basketball player in the US, Olivier Rioux (7 feet 9 inches, 2.36 meters) wears a size 20.

In fact, Robert Wadlow took a job marketing shoes for a particular shoe manufacturer. Part of his annual compensation was a certain number of pairs of custom shoes.

I mention all of this because if you were to hop in your time machine and talk with Robert, and he happened to mention his difficulty in finding shoes, the correct response is not “Well, we’re all a little bit tall.” Or “I know exactly what you mean. I’m a size 8.5, but a lot of stores don’t carry 8.5, so I have to try on the size 8 and the size 9 to see which one fits better. It’s so annoying.”

Robert didn’t like being in a crowd of strangers because people were constantly sneaking up behind him with pins, needles, and other sharp objects so that they could stab him in the leg to “prove” that we wasn’t really that tall. They wanted to “prove” he was using stilts. Again, if Robert told you this story, the correct response is not “I know. Crowds can be difficult for me too.”

We’re not all neurodivergent. We’re not all a little bit autistic. We’re not all a little bit ADHD. That isn’t what the term “spectrum” means.

If I tell you how difficult it is for me to maintain eye contact with someone, and you say “I know how you feel,” there’s a very strong chance that you have no idea how I feel. And saying that you do doesn’t come across as empathetic. It comes across as clueless (at best), patronizing, demeaning, or dismissive.

You and I are not the same. Your neurotypical world goes to great lengths on a daily basis to make sure I know that my autism and ADHD are considered wrong. To tell me my autism and ADHD are problems to be solved. To tell me that I need to just “get over it.” To tell me that I have a disease and need a cure.

I don’t need you to understand how it feels for me to make eye contact with a stranger. I need you to accept that it is difficult for me. I need you to accept the fact that I may not make as much eye contact as you might like. I need you to accept what I am saying. I need you to accept me.